Thomas Edison, the inventor of the phonograph, is often thought to have produced the first sound recording. But in reality, nearly 20 years earlier, it was a different invention from a Frenchman that laid the foundation for sound recording as we know it today.

In this article, we walk through the timeline of the very first sound recordings and look at how modern technology helped us finally listen to the earliest captured sounds.

A TIMELINE OF THE FIRST SOUND RECORDING

Thomas Edison’s phonograph is legendary — and for good reason. It was the first machine that could capture and play back sound.

But when it comes to the very first sound recording, Edison isn’t our man.

1857: EDOUARD-LÉON SCOTT DE MARTINVILLE’S PHONAUTOGRAPH

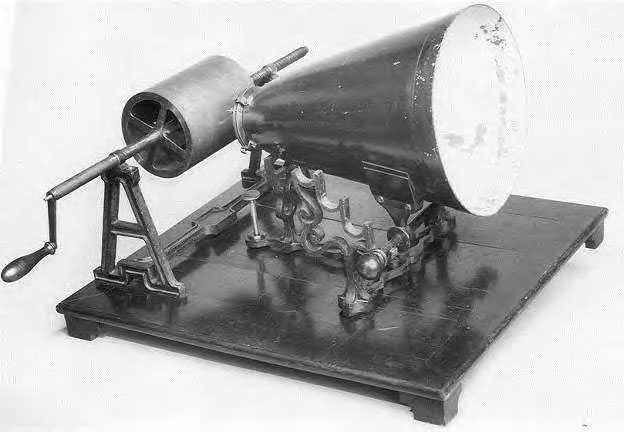

In 1857, a French inventor named Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville built a device called the phonautograph. It was designed to visually capture sound waves, but could not play them back. Imagine a seismograph, but for sound instead of earthquakes.

Here’s how it worked: A horn collected sound and funneled it to a thin membrane, which vibrated when sound waves hit it. Attached to the membrane was a stylus that traced those vibrations onto a moving surface (usually paper coated in soot).

The phonautograph created visual squiggles, or waveforms of sound. You couldn’t hear them, but you could see that sound had been made. Scott used the device to record short snippets of speech. He was mostly interested in studying the science of sound, not creating something for entertainment.

You can actually listen to some of his early voice notes here, which scientists were able to recreate from his waveforms.

1860: RECORDING “AU CLAIR DE LA LUNE”

In 1860, Scott used his phonautograph to trace a recording of someone (possibly himself) singing the French folk song “Au Clair de la Lune.” The waveform he captured was fragile — just lines on paper — but it’s often cited as the earliest recognizable record of the human voice ever recovered.

But again, it couldn’t be played back. As we know, Scott never designed the phonautograph to reproduce sound, only to capture it visually. And for nearly 150 years, that piece of paper with his recording gathered dust in the archives, until modern technology brought it to life.

In 2008, audio historians and scientists managed to scan and digitally interpret the waveforms from Scott’s original recording and recreate the audio. The quality is scratchy and sounds like a ghost, but it’s an unmistakable recording of someone singing Au Clair de la Lune.

1877: EDISON’S PHONOGRAPH

Fast forward two decades after Scott’s recording, and along comes Thomas Edison with a brand-new invention: the phonograph.

Unlike the phonautograph, Edison’s device didn’t just visualize sound, but could play it back.

The phonograph used a diaphragm and stylus to etch sound vibrations onto a rotating cylinder covered in tinfoil (and later, wax). When someone spoke or sang into a mouthpiece, the sound waves made the diaphragm vibrate, which moved the stylus and carved grooves into the foil.

To hear it back, you’d simply run the stylus over the grooves, and vibrations would travel back through the diaphragm and recreate the original sound. The audio was scratchy and low-quality, but it worked. For the first time, people could actually play back a captured sound.

1890s: EDISON-DICKSON’S KINETOPHONE

By the 1890s, Edison moved on to his next project: moving pictures. With his assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, he created the Kinetoscope, a peephole-style film viewer. From there, they combined it with the phonograph to create something even more ambitious: the Kinetophone. This invention could synchronize sound and film to create the earliest version of a talking movie.

The first known example of the Kinetophone being used was filmed in 1894 or 1895 and is called the Dickson Experimental Sound Film. In it, a violinist plays a melody while two men dance in the background. The sound was recorded separately on a cylinder, and the two were meant to be played back in sync.

It was a clever idea, but just like the phonautograph, it had serious limitations. Synchronizing the film and audio was incredibly difficult, so it often played out of whack. Though the Kinetophone never really took off commercially, it laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the modern motion pictures we know and love today.

SO, WHEN WAS SOUND FIRST RECORDED?

It depends on what you mean by “recorded.”

If you’re talking about the first time sound was captured in any form, even if no one could hear it, the credit goes to Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville and his phonautograph in 1857. His recording of Au Clair de la Lune in 1860 is the oldest known record of a human voice and song, even though it couldn’t be played back for 150 years until scientists worked their magic.

But if you’re asking about the first time sound was captured and played back, then we must look to Thomas Edison with his phonograph in 1877. His invention gave us the first way to listen back to a recording.

Either way, both have been significant milestones in the history of sound recording. Without Scott’s vision or Edison’s innovation, sound recording as we know it could look very different.

THE POWER OF DIGITIZING AUDIO

The fact that scientists were able to digitally resurrect Scott de Martinville’s 1860 recording in 2008 is an amazing feat. Modern technology helps not only to preserve history but give new life to moments that might have otherwise been lost forever.

It’s a reminder that the sounds we care about on a personal level — like family stories, and old voice recordings — deserve to be cherished and protected for future generations.

At EverPresent, we specialize in digitizing old audio recordings that might otherwise fade away. Our audio digitizing technicians transfer over 10,000 hours of audio tapes, vinyl records, and reel-to-reel cassettes every year.